Visit us on Facebook Visit us on Facebook

|

Skipjack Herring, Ghost Fish of the Upper Mississippi

By John Lyons

March-April 2019

|

|

|

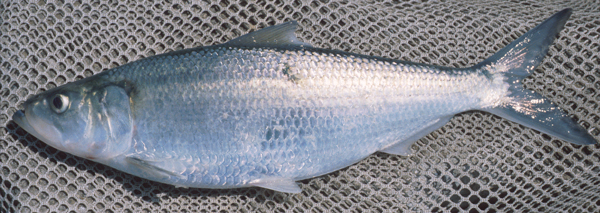

Skipjack herring. (John Lyons) |

The rapid disappearance of the skipjack herring from much of the Upper Mississippi system over 100 years ago is a cautionary tale of the unanticipated consequences of building dams on the river.

I cast my jig into the strong current and began reeling it in rapidly, near the surface. I saw several flashes below it, then suddenly a silver form rocketed up and grabbed the bait. Its momentum carried it into the air, but it was well-hooked and a high-speed battle began. The fish zigzagged and leapt into the air. I wasn’t sure I could land it with my light tackle, but after a few minutes it tired and I was able to net a 16-inch, 1.5-pound skipjack herring (Alosa chrysochloris), my first ever. I was ecstatic, hooting, hollering and dancing around on the riverbank. It was the beginning of some memorable fishing, as over the next couple of hours I caught a half dozen or so large skipjacks and lost many more. Their fighting was spectacular.

I wish I could say this happened on a river somewhere in the Driftless Area, but I was fishing on the Cumberland River in north-central Tennessee. However, if I had been around in the early 1900s I could have enjoyed the same experience on the Upper Mississippi River and many of its larger tributaries — but no longer. The rapid disappearance of the skipjack herring from much of the Upper Mississippi system over 100 years ago is a cautionary tale of the unanticipated consequences of building dams on the river.

The skipjack herring is a member of the herring family (Clupeidae) and is related to the shads, alewives and the ocean herrings of pickled-herring fame. Like most herring, it is a streamlined, silvery fish. The skipjack reaches a maximum size of about 20 inches and three pounds, and an age of about four years. It is primarily a river fish and prefers moving water, actively swimming throughout the water column, often in schools. It spawns in spring in large rivers, and a female may produce 100,000 to 300,000 eggs. Eggs are broadcast and fertilized on sand and gravel river bottoms with strong current, where they hatch a few days later. Skipjack fry feed on plankton, juveniles eat aquatic insects, and adults are top predators, mainly eating fish.

Anglers are interested in skipjack herring as a sport fish rather than a food fish. Skipjacks are very bony and are not normally eaten. As early as 1908, biologist George Wagner, writing about the fishes of Lake Pepin in the Transactions of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters (Vol. 16) states: “Although worthless as food, the skipjack is not to be despised as a sport fish. I consider him quite the equal, in fighting powers, of the black bass of these waters.” In their treatise Northern Fishes (1974, U. of Minnesota Press), Samuel Eddy and James Underhill write: “The angler finds it a savage fighter on light tackle.” In Ohio, Milton Trautman (1981, The Fishes of Ohio, Ohio State University Press) notes of the skipjack: “It readily took natural and artificial baits, leaping spectacularly in the air and dashing about with great speed when hooked. When taken with the aid of a fly rod and light tackle it ranked among the finest of Ohio game fishes.” In Tennessee, the skipjack is sometimes known as the “Tennessee tarpon,” and anglers target them in the spring when they gather in dam tailwaters to spawn.

The near complete demise of the skipjack herring throughout Minnesota, Wisconsin, and much of Iowa and Illinois can be attributed to the completion of the Keokuk (Iowa) Dam, also known as Lock and Dam 19, in 1913. This large hydroelectric dam is almost a total barrier to upstream fish movement, though a few fish appear to use the lock to get above the dam.

When the dam was completed, the migratory nature of the skipjack was poorly understood, but it soon became clear that a seasonal migration was essential to the presence of skipjack in the watershed above the Keokuk Dam. Apparently, skipjack spent the winter in more southerly areas of the Mississippi, possibly as far south as below the mouth of the Ohio River. In spring they migrated upstream as far as they could go, in the Mississippi River up to St. Anthony Falls, in Minneapolis; in the Minnesota River to Big Stone Lake, on the Minnesota-South Dakota border; and in the St. Croix River up to the St. Croix Falls Dam, on the Minnesota-Wisconsin border.

Spawning took place in these upper areas later in the spring, then adults and their offspring spent the summer feeding and growing. In the fall, the skipjack moved back downstream to their overwintering areas. Presumably winters in the Upper Mississippi were too harsh for skipjack. When the dam at Keokuk was complete, this migration was blocked. Within just a year the upstream population had nearly collapsed, and by the 1950s, after the completion of many additional dams on the Mississippi, the species was believed extirpated above Keokuk.

The disappearance of skipjack herring did more than eliminate a fine sport fish from much of the Upper Mississippi River system. The skipjack served as the only host for the glochidia, or larva, of two common and important mussels, the ebony shell (Fusconaia ebena) and the elephant-ear (Elliptio crassidens) mussels. The ebony shell was the most valuable species for the pearl button industry on the Upper Mississippi. These two mussels are long-lived, and their populations persisted above the dam longer than the skipjack, but within a decade it became clear that no new ebony shells or elephant-ears were being produced, and their populations quickly dwindled. A handful of these mussels still exist above Keokuk, believed to be elderly survivors from before the dam, but they are the last of their kind in this part of the river system.

Although the large schools of more than a century ago are long gone, a few skipjack herring are occasionally found upstream of the Keokuk Dam. These ghosts of the past are most likely to be seen in wet years, when river flows are high and dam gates are out of the water for extended periods. The Keokuk Dam is still a complete barrier, even at flood stages, but presumably at high flows it’s easier for skipjack to use the lock to bypass the dam. In 1986 and again in 2011 a few young-of-year skipjack were collected in Wisconsin-Minnesota boundary waters, indicating successful reproduction. Thus, the habitat above Keokuk remains suitable, but these skipjack headed south in the fall and were unable to return the next spring, as none were found above the dam in 1987 and 2012.

As long as the Keokuk Dam and other mainstem dams remain, it seems unlikely that skipjack herring will return to the Upper Mississippi. Proposals to build fish passages at the dams for migratory species such as skipjacks have ground to a halt over fears that bighead carp, silver carp and other invasive species would use them.

Although most living river anglers have no idea what was lost when skipjack disappeared, I for one mourn their absence. And, when the spring fishing season rolls around, I’ll wish the Cumberland River was a lot closer.

John Lyons is curator of fishes at the University of Wisconsin Zoological Museum, Madison. His last story for Big River was “Mysterious Eels and Blood-Sucking Lampreys,” July-August 2018.

March-April 2019 copyright © Big River Magazine

|