|

Upper Mississippi Wine

|

|||||||

|

2009 Update: The Upper Mississippi River Valley is now an American Viticultural Area (AVA) What does river bluff geology have to do with the flavor of Upper Mississippi wine?

Big River is an independent magazine about the people, places, life and events on the Upper Missisippi River. "The limestone in the soil here could be discernable, especially in the white wines. After all, Chablis wines from northern France are known for their ‘flinty’ taste." |

In 1973, when David Bailly planted French grape vines in a farm field near Hastings, Minn., he was following a dream and taking a big risk. No one had yet managed to get French hybrid vines to survive bitter Northern winters, let alone produce plentiful grapes and good wines. Thirty-two years later, the Alexis Bailly Vineyard and Winery is the oldest and largest in the Upper Mississippi Valley, producing more than 60,000 gallons of wine a year, but it’s not the only one anymore. Dozens of new wineries have grown up near the Upper Mississippi and its tributaries. Convinced that the area has unique characteristics for growing grapes and making wine, they are banding together to apply for federal designation as an American Viticulture Area, based on the distinct topography, soils, bedrock and microclimates of the “driftless area” of the Upper Mississippi River. Good for a Cold Climate The Alexis Bailly Vineyard is located on a wide sandy plain between two river towns of Hastings and Red Wing. Before European settlement the plain was probably oak savanna. Now it is mostly farmland. Owner and winemaker Nan Bailly, daughter of David Bailly, says the location is ideal for growing grapes. “This whole area is sandy glacial outwash. Grapes do very well in sandy soil. They need good drainage.” The driftless area has a lot of sandy soils, but to survive in the North, the French hybrid grapevines that Bailly planted, such as Maréchal Foch and Seyval, require an enormous amount of care. They must be taken down from their trellises in the fall; pruned, pinned and carefully buried under soil or mulch; then resurrected each spring and guided back up on the trellises again. Even so, they are sensitive to cold. A recent icy, snowless winter killed off many of the French vines at the Bailly vineyard, which Nan Bailly is now replacing with new cold-hardy hybrids from the University of Minnesota. “French vines have been the backbone of our winery for 30 years,” Bailly said. “With the new hybrids I will still be able to maintain the same styles of wine. I just won’t have to bury all those vines every year!” Many new wineries rely on these new cold-climate grape varieties developed by legendary horticulturist Elmer Swenson of Osceola, Wis., and the University of Minnesota. They resist disease, withstand winter temperatures down to –20 or even –40 degrees Fahrenheit, ripen early and, most important, taste good. Coincidentally, many of the new hybrid grapes are named after places on the river, such as La Crosse, La Crescent, St. Pepin, Frontenac, Frontenac Gris and St. Croix.

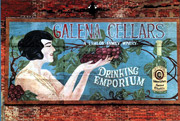

Falconer’s seven-year-old vineyard fills a shallow valley that once was an alternate riverbed of the Mississippi. The nearby river and the surrounding hills moderate temperatures. It’s a good place to grow grapes. Falconer started the winery after selling his previous business, Red Wing Stoneware. “After I retired, we were looking for something to do with the land we’d bought. We’d always pulled out wild grapes like weeds up here, but it was a while before we realized, ‘This land wants to grow grapes!” Falconer said. This year, his third release, the winery will produce about 1,600 gallons of wine. A Change of Latitude It’s part of the mystery of winemaking that the same grapes have such different qualities and flavors when grown on different soils under different conditions. Dubuque, Iowa, and Galena, Ill., are about 275 miles downriver from Hastings and Red Wing. These few miles make a big difference when it comes to growing wine grapes. Winters are milder, spring starts earlier, summers are hotter, and the fall lasts longer. “The new hybrids are growing like crazy this year — much better than the older ones did,” said Chris Lawlor, winemaker at Galena Cellars Lawlor Family Winery at Galena, Ill.

Seventeen-year-old Eric, Chris Lawlor’s son, is one of many family members involved. Next year he plans to go college at Fresno State University in California, to study enology (winemaking), as his mother did years ago. A cousin may also go there. “It seems they have a passion for it. It’s exciting to see what they’ll come back with. We have an intensive lab program set up here already,” Chris Lawlor said. “I think if we have the right technology, we can grow some really premium wines here.” Galena Cellars sells most of its 60,000 gallons, or 300,000 bottles, at its shop in downtown Galena, a town with a tourist buzz that lasts all year long. Location is very important for regional wineries with local distribution. Eagles Landing Bed & Breakfast and Winery in Marquette, Iowa, has a great location for drawing visitors — it’s on the river, just upstream from the Marquette-Prairie du Chien bridge and the Isle of Capri Casino. The winery and storefront are downtown. Being on the river has given them a big marketing advantage, said owner Roger Halvorson. When he and his wife, Connie, started out with two acres of grapes six years ago, it was a retirement project. “I was just going to retire and grow some grapes,” Roger Halvorson said with a laugh. “We started the inn because we wanted to meet new people. Now we’re booked up through the fall and into next year.” The state of Iowa is helping promote local wineries with “Iowa Wine Trail” events this fall at Eagles Landing and five other wineries and a cidermaker in eastern Iowa. Idle Land Makes Good Also on the Wine Trail is Park Farm Winery, a new winery 15 miles west of Dubuque, Iowa. Everything here is new, from the architect-designed main building that resembles a modern chateau on a hill, to the stainless steel winemaking vats that were installed in time for the first harvest in 2004, to the designer details of the winetasting room. Park Farm’s inspiration is old Europe, but it clearly aims to be an upscale event facility and a destination for tourists from Dubuque and beyond. David Cushman, general manager and family member, said the idea originated when the family was looking for something to do with idle land, some of which was just coming out of the Conservation Reserve Program. “My mother ran into a viticulture agent at the hardware store,” he said. “She couldn’t believe it could be done. Then she did some research.” Massbach Ridge Winery, near Elizabeth, Ill., had a similar beginning. “We were looking for an alternative to traditional farming,” said winemaker Peggy Harmston, who has a farming background, “but we wouldn’t have gotten into growing grapes without help from the University of Illinois agricultural extension agent.” Six years after planting their first vines and one year after releasing their first wines, she is happy with their prospects. “We’ve had good luck so far. The land here is ideal for growing grapes. We have a south-facing, gentle slope that sits high up, so we escape the late spring frosts. And we’re close to Galena, which is a tourist center.” Agricultural extension agent Tim Rehbein of Vernon County, Wis., has encouraged many new vineyards. Federal supports for tobacco growers of southwestern Wisconsin were being phased out in 2000, so Rehbein started a program to help them shift from tobacco to grapes. Today, there are more than 50 acres of grapevines in the area. Farmers sell their crops to Northern Vineyards, a grape-growing cooperative in Stillwater, Minn., or to Eagles Landing Winery in Marquette, Iowa. At three or four tons per acre, bringing a price of $750 to $1,000 a ton, farmers are replacing their lost income. “It’s working out pretty well. Tobacco farmers are good at getting out in the field and doing labor-intensive crops, although grapes are harder, since they grow on the hillsides,” said Rehbein. “One farmer who was a longtime smoker came in here and said, ‘I’m going to have to quit smoking if I’m going to grow grapes.’ And he did! He never smoked again.” Taste the Geography To promote the industry, wineries and vineyards are applying this fall for federal designation as an “American Viticulture Area” (AVA), recognizing it as a distinct grape growing area. Napa Valley is one of the most famous in the United States. The Ohio River Valley is the largest. The proposed Upper Mississippi AVA encompasses the whole “driftless area” (see map). “An AVA is based on the geography of the land, its soils and subsoils and the microclimates,” Rehbein said. “Soils in the driftless area are primarily silt loam and clay loam on limestone bedrock. You go one county east of here and you don’t find that. You find a lot of clay soils on granite bedrock.” The driftless area’s hills and valleys are good for grape-growing for other reasons. The slopes keep the air moving. The hills catch the sun’s warmth. This creates what the French call “terroir,” which is the distinctive taste and characteristics of products grown in a specific place. So, could a discriminating wine drinker tell an Upper Mississippi River wine from one grown in New York or New Mexico? Wine judge and writer John Breitlow of Winona thinks it’s quite possible. “The limestone in the soil here could be discernable, especially in the white wines. After all, Chablis wines from northern France are known for their ‘flinty’ taste,” he said. The flinty taste derives from the limestone mineral soils in the area. “Keeping the limestone taste would be the winemaker’s choice, of course. Storing the wine in oak barrels, for example, would overwhelm the flinty taste,” said Breitlow. “Winemaking is more art than science, and it’s very complicated.” That’s another mystery — how winemakers take the same grapes, grown in the same region on similar soils, and create such very different wines. This you’ll have to taste for yourself. Copyright 2005 Open River Press Pamela Eyden is news and photo editor for Big River. |

||||||